Before we jump into the new and improved Raw Converter, we should spend

a little more time looking at the files (photos) that your camera creates. Digital

photographers are faced with a seemingly endless array of choices on their

cameras. Many of these options are worth exploring to enhance image quality, but a

great many only affect shooting convenience. Following are several features that

will affect how you work with your file in the Raw Converter. Other choices, such

as exposure, metering modes, Auto Focus, and Drive Mode, are critical to the making

of fine photographs, but the following represents aspects of the file that are relevant

to the processing of the image. Of course, this is just a partial list of features and

options, but they are the ones most photographers think about every time they pick

up the camera.

• ISO

• File Format

• White Balance

• Picture Styles or Camera Settings

ISO

ISO (International Standards Organization) is a rating that refers to how sensitive

the sensor is to light. ISO 100 is considered to be slow, whereas ISO 1600 is considered

to be fast. A slow ISO setting means your sensor is not really sensitive to light,

so it needs a lot of light to form an image. This means you need either a slower shutter

speed such as 1/30 or 1/60, or a larger aperture such as f4 or 5.6. When your sensor

is really sensitive (ISO 1600), you can use faster shutter speeds (1/250, 1/500) or

smaller apertures (f16, f22) to create the image.

So why not just put it on 1600 all of the time? One word: quality. The higher the

ISO, the more likely you are to experience noise in your photographs. Noise is the

digital equivalent of film grain just not as pretty. A sensor really only has one sensitivity.

If your camera’s lowest ISO is 100, then that is your real sensitivity. If 200 is

the lowest, than that is your actual sensitivity. To enable a higher ISO or sensitivity

to light, the camera must pass more power through the sensor. This extra power creates

noise in the resulting file. At best, noise can look like small specks of grain; at

worst, it takes on the appearance of an undesirable pattern. As you will see later in

the chapter, the Raw Converter can help reduce noise in your photographs, but it

will come at a cost.

Depending on your camera model, noise can begin to appear even at ISO as low

as 400. To see where you begin to get noise on your camera, simply take the same

shot with all of the different ISOs that your camera provides, and examine them in

Photoshop at the view setting of Actual Pixels. You will quickly see which ISO setting

causes noise.

File Format and Bit Depth

When it comes to choosing a file format for your camera, JPEG and Raw are your

primary choices (see Chapter 1 for more information).

Let’s review the differences.

• The JPEG format will compress your file so that more images can fit onto a

memory card. On most cameras, there are different degrees of compression that

deliver various degrees of quality. The highest quality JPEG setting will produce

exceptional images due to the fact that there is a minimal amount of compression

taking place. The camera is just “saving” the file in this format. It is using

the same resolution as the Raw setting, assuring maximum image quality.

• The Raw format on the other hand, applies no compression to your image. It simply

takes the data off of your sensor and sends it to the card unprocessed and uncompressed

(sort of . . . there is a little compression, but nothing to worry about).

• JPEGs are processed faster in the camera, so you can shoot faster. Raw images

take longer to shoot and process.

• JPEGs are immediately ready to use in other applications. Raw images must be

“post processed” first.

My recommendation is for photographers to shoot using the Raw format. If,

however, you have a camera that does not support this format, the good news is

that Adobe has upgraded the Raw Converter in CS3 to accommodate JPEGs as well!

This means that JPEGs now have access to the same streamlined image-processing

software that Raw images use, The Adobe Raw Converter.

White Balance

With your digital camera, white balance is the equivalent of filtering for different

light sources or choosing a designated film to match the light source. For example, if

you use a daylight-balanced film (the most common type of film) under tungsten

light (a typical light bulb), your image will have a heavy orange cast. This is because

tungsten bulbs give off an orange/yellow light. To correct for this, you would buy

tungsten film to shoot in this situation. This would produce an image with a neutral

color cast. You could also put on a Tungsten Filter to correct for the orange light. This

filter would be blue.

In digital cameras (and in the Raw Converter), the white balance setting can do

all of this for you. You merely have to change the setting. When you are shooting

under tungsten lights, you choose the tungsten setting. If you find yourself shooting

under fluorescent lighting, choose the fluorescent setting. It’s easy as pie. In the past,

it was recommended that when shooting JPEG you should set your white balance

on your camera rather than in Photoshop. This is still a good idea. However, now

that that you can open any file into the Raw Converter, you may find it easier to set

the white balance in the Raw Converter rather than at the time of shooting.

Some common white balance settings found on both digital cameras and as presets

in the Adobe Raw Converter are Daylight, Auto, Cloudy, Shade, Tungsten,

Flash, Fluorescent, Kelvin and Custom.

Auto white balance will try to balance the scene for you. This works for average

types of indoor photography. There are better ways of achieving a good white

balance, so reserve the use of this setting for when you are unsure of the light

source, for example, when using indoor lighting. Is it tungsten, halogen, or a mix of

lighting? If you are unsure, simply set your camera on Auto White Balance Mode.

Chances are good that you will end up with very good results.

Daylight will give you good results under . . . well . . . daylight conditions. It

will also give proper results during sunsets, sunrises, and night scenes. In any situations

where you would use daylight film, this setting will be appropriate.

Flash is designed to give you good color when you are using the on camera

flash. It adds in a little yellow/orange to combat the overly blue light of the flash.

Consider using the cloudy setting instead of this one, however, to add more warmth.

Cloudy will also add orange/yellow to your picture. Typically, the added orange

cast is a little heavier than that of the flash setting. Cloudy days usually produce a

significant blue cast.

Open Shade adds even more orange/yellow than cloudy. The light found in

open shade is very blue.

Tungsten adds a strong blue cast to overcome the heavy orange coloration of

tungsten light sources.

Fluorescent will add a slight magenta color to balance the overall green cast of

this light source.

Kelvin is a setting found on higher-end cameras and can drastically change the

color balance of your image. The higher end of this setting (8000) will add a lot of

warmth, while the lower end (2000) will significantly cool down your image with a

lot of blue. The Daylight White Balance setting on a camera is considered neutral. It

usually falls within the 5200–5500k range. The Kelvin setting on the camera is

mainly designed for people using a handheld color meter. Try experimenting with it

to learn more about the color and temperature of light.

Custom is the most accurate of all of the settings. You can use this setting to

produce a very exact neutral cast in any lighting situation. Think of the other settings

as close but not quite perfect. All light sources are slightly different, and it

would be impossible to create a “preset” for all of them. To use this setting, you must

first take a picture of a gray or white card in the light source you want to shoot. The

camera will then balance the card back to neutral and store this setting. You then

choose Custom from your white balance option and it will revert back to the stored

setting. Anytime you are under a light source other than daylight, you should use

this setting. Look to your camera manual for exact directions on how to use the

Picture Styles and Camera Settings

Another great feature of the digital camera and the Raw Converter is that it can reproduce

the look of many film types! In the Raw Converter, just moving a few sliders can

change the feel of your photograph. When working with film cameras, if we wanted to

take a portrait, we would choose a film with low saturation and low contrast. This film

would have a neutral or warm color cast to it. For general shooting, landscapes or architecture,

you could use a film that produced higher contrast and deep color saturation.

With digital cameras, instead of buying different films for each situation, we can

simply set the camera to mimic the type of film we want to use. By applying a picture

style such as Portrait or Landscape, the camera will change its settings such as

saturation and contrast to fit with the image you want to create. With most cameras,

you can even go in and adjust these settings yourself. With the Raw Converter, you

also have control over the look of your image. Simple sliders allow you to remove or

add contrast, brightness, or color saturation.

Let’s take a look at the way a digital camera creates an image.

The sensor will capture the image information. At this point, the image data is

raw, meaning it has not been changed at all. It then sends this raw information on

to the camera’s processor. In the processor, it will undergo changes, which are dictated

by the way you set your camera. These settings could include File Format,

JPEG Compression Setting, Color, Contrast, and Saturation. If you had your camera

set to shoot a picture style such as Landscape or Portrait, your camera will also apply

the individual settings that these styles represent.

It is in this stage that your camera keeps your file as Raw or changes it to a JPEG.

When shooting in JPEG, any settings that you have set on your camera such as contrast

or color tone will be permanently applied to the image. The processor will take

these settings, apply them to the Raw image information, and then turn this information

into a JPEG file.

If you are shooting Raw, these settings get recorded as a set of instructions or directions

on how the image should appear when it is opened. They are not permanently

applied. These directions can always be changed to suit your needs without

any degradation to your file whatsoever. You can always return to the default settings

as well. After these settings are applied, the processor sends the information to

the compact flash card for storage.

The long and short of the situation is this: If you are shooting in JPEG it is more

important to adjust these settings before shooting. When shooting in Raw, these adjustments

can be set in the Raw Converter afterwards.

16-Bit Images

So why is it more important to make adjustments in the camera for JPEGs? Bit

depth. Bit depth describes the amount of shades or tones a pixel can contain. An 8-bit

image contains 256 shades of gray in each channel, whereas Photoshop’s 16-bit

image contains approximately 32,768 shades in each channel. The reason it’s 32,000

and not 65,000 is that technically Photoshop uses only 15-bit color, but for the sake

of clarity, we will call it 16-bit from here on. The result of more shades of gray in

each channel is smoother gradations in the images, which results in reduced posterization

and banding (a harsh, unnatural transition in color) in viewed and, even

more noticeably, in printed images.

To take advantage of the denser 16-bit features, the images must be captured in 16-

bit color. Taking an 8-bit image in Photoshop and choosing Image > Mode > 16

bits/Channel does not magically convert an 8-bit image to 16-bit. Photoshop cannot

add color information that was not captured. Cameras that support the Raw format are capable of shooting images in high bit depth such as 10-, 12-, or 14-bit. Once they

arrive in Photoshop, they automatically convert to 16-bit. This conversion does not in

any way degrade your image. So, again for simplicity, we can consider that our cameras

capture an image in high bit depth. This is important because this high bit depth is excellent

for making adjustments and corrections to the images. The extra data helps the

image maintain integrity while adjusting it. An 8-bit image can become posterized very

quickly, whereas a 16-bit image is much more robust because of the extra image data.

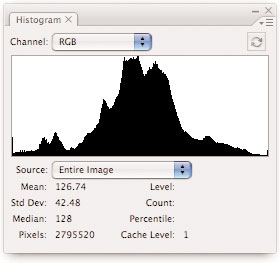

Figure 2.1 shows a histogram of an image that is in need of a typical adjustment

to increase contrast.

FIGURE 2.1 A typical histogram.

FIGURE 2.1 A typical histogram. Figure 2.2a shows an 8-bit histogram after the adjustment, and Figure 2.2b

shows the 16-bit histogram after the adjustment. Notice the gaps in the 8-bit histogram?

These gaps indicate that there is no image data available. The result would

be posterization or a very harsh transition of color gradient in the image. Histograms

and image correction are covered in more detail in Chapter 4, “Tonal Corection and

Enhancement.”

The disadvantage of a 16-bit image is file size. A 16-bit image’s file size is double

that of an 8-bit image. After you begin to modify the image and add layers, the file

size can grow very quickly. If you have a fast computer with a lot of RAM and plenty

of storage, you may decide to keep the images in 16-bit. If you are working with limited

computing resources, a good practice is to perform the image corrections, such

FIGURE 2.2A The adjustment with 8-bit

FIGURE 2.2A The adjustment with 8-bitreveals gapping.

FIGURE 2.2B The adjustment with 16-bit

FIGURE 2.2B The adjustment with 16-bitexhibits no gapping.

.

as ast

________

as tonal adjustments and color correction, in the Raw Converter and then when you

open the image into Photoshop, convert to 8-bit. Directions for this will be covered

later in next post.

0 comments:

Post a Comment